Chapter 7

Links with the Rutson Family

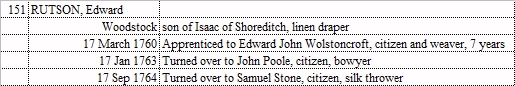

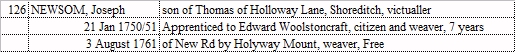

The Public Record Office at Kew has an excellent web-site where there is a searchable catalogue of a large proportion of their holding of records. It is quite easy to find the reference for an item that interests you before visiting the repository; you can even order it on-line ready for your visit. By using this facility, I was able to locate the documents relating to a suit brought against Edward Woolstonecraft by Isaac Ruttson. The case, entitled "Ruttson v. Woolstonecroft", was brought in the Court of Chancery in 1744 and the PRO reference is C 12/2242/33.1 Despite its title, throughout the pleadings Edward’s name is spelt "Woolstonecraft". Legal disputes between different parties are settled by civil litigation. The Public Record Office holds a great many legal records of such litigation settled in the courts of equity providing a wealth of information. The main court of equity was the Chancery. Proceedings would follow a similar pattern; after the plaintiff had submitted a written document setting out in full his complaint, the defendant would present his answer. Other submissions would follow, including the plaintiff’s replication and the defendant’s rejoinder. Witnesses might be asked questions and answers given. All the papers relating to the suit and any evidence would be delivered to one of the Masters in Chancery for examination. Once he had made a formal report to the Chancellor, the latter would issue his decree and order.2 On 28th September 1744, Isaac Ruttson submitted his Bill of Complaint to the Right Honourable Philip, Lord Hardwicke, Baron of Hardwick, Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain. Isaac was acting as orator on behalf of his nephew, Richard, who was a minor, about seven years of age. Richard was the son of Isaac’s late brother, also called Richard, who had died on 10th February 1741/42, apparently intestate. He had left a widow called Elizabeth, together with four children. The eldest was Elizabeth, the child of a former marriage. The younger three were Isaac, Mary and Richard, the children of his marriage at the time of his death. Richard had left property in Pinner, Middlesex, from which he was receiving rents. This real estate would be inherited by his son Richard as his "Heir at Law". However, Richard also left debts, one of which was, apparently, to Edward Woolstonecraft in the sum of £100. The loan had been taken out in November 1741, very shortly before Richard’s death. Isaac made some very serious accusations against Elizabeth. He claimed that, after her husband’s death, she had obtained letters of administration to enable her to manage the estate herself. He alleged she had received the income arising from the property but, instead of clearing the debts, had: "Wasted and converted to her own use all the Personal Estate of the said Intestate". He maintained she had obtained a loan by mortgaging the property and put the advance towards debts she was accumulating herself. He insisted she was trying to make as much money out of the property as she could and would waste the inheritance to such an extent that her son would receive no benefit from it whatsoever. Furthermore, Isaac criticised her treatment of her children: "The said Elizabeth taking Advantage of your Orators Tender Years hath by all possible Ways Contrived and Cast about how she might Charge and Dispose of the said Real Estate for her own Advantage and for the Payment of her own Debts to the Great Prejudice of your Orator and not only so But the said Elizabeth hath Greatly Neglected the Education of Your Orator and his Brother and two Sisters in so much that unless the Management of Your Orators Person and Estate is Taken out of her hands Great Detriment and Prejudice is Likely to Ensue to Your Orator both with Regard to his Estate and the Care and Education of his Person". Isaac went on to assert Edward Woolstonecraft and others had conspired with Elizabeth and added: "And that she takes no manner of Care of your Orator or of his Education or of the Education of his Brother and two Sisters but sometimes Threatens that she will turn them out of Doors to shift for themselves and in many other respects acts in a Manner unbecoming a Parent All which Actings and Doings of the said Elizabeth and the rest of the Confederates are Contrary to Equity and Good Conscience And lend to the Manifold Wrong and Injury of your Orator." Isaac wanted Elizabeth Ruttson and Edward Woolstonecraft, together with their other supposed confederates, to appear before the court to answer the complaint. He asked that Elizabeth be ordered to confirm that her husband had left no will and to provide a full account of her husband’s estate, including the debts and whether they had been paid. He also requested proof of Edward’s debt:

"And that the said Edward Woolstonecraft may set forth how and in what Manner and by what Security his said Debt arises and whether any and what part thereof hath been paid and by whom and when and how much thereof now remains due". Additionally, with the Deeds and Writings pertaining to the property to be produced in court, he wanted the court to authorise him, or another appointed by the court, to receive and take responsibility for the income from his late brother’s property: "And that the said Isaac Ruttson Your Orators Uncle or such other Person or Persons as the Honourable Court shall think fit may be let into the receipt of the Rents and Profits of the said Real Estate to receive and Take Care of the same for the Use and Benefit of your Orator". Finally, he wanted custody of his nephew: "That the Care and Education of your Orator may for the Reason aforesaid be If Isaac’s complaint were true, he would have been well justified in bringing the case to court. Even so, the possibility should be considered that Isaac may have been acting in his own interests to get control of his late brother’s estate and using the action to effect his aims. There is some indication in the Entry Book of Decrees and Orders that Isaac Ruttson may have succeeded in his complaint. At reference C 33/384, p 11,3 on 20th November 1744, with the plaintiff given as Richard Rutson and the defendant as Elizabeth Rutson, it seems that Elizabeth failed to appear after having been ordered to do so for not answering the complaint. A later entry at reference C 33/384, p 70, on the 19th December, with the plaintiff as Richard Ruttson and the defendant as Elizabeth Ruttson, shows that she failed to appear once more. Whatever the outcome of the suit, it is doubtful whether Edward ever saw his loan of £100 again. Assuming that the spelling variations can be ignored and the case was between Edward Wollstonecraft and his son-in-law, the whole affair would doubtless have caused a degree of animosity between them. This could have been a reason why Edward wanted to make absolutely certain there was no way by which Isaac could seize the legacy of his wife, Elizabeth Ann. From the information in the court case and Edward’s will, the following family tree seems likely:

|